Understanding PBC and today’s treatment landscape

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a chronic autoimmune liver disease marked by immune-mediated damage to the small bile ducts inside the liver. Over time, that injury can lead to cholestasis (reduced bile flow), progressive scarring, cirrhosis, and in advanced cases, liver failure or transplant.1-4

PBC is considered a rare disease, but its impact is not small. A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis estimated a pooled global prevalence of 18.1 cases per 100,000 people and an incidence of 1.8 per 100,000 person-years, with higher prevalence among women and variation by geography.3 In the United States, population estimates also show a strong sex disparity. NIDDK summarizes that in 2014, prevalence was estimated at 58 per 100,000 women and 15 per 100,000 men, and the average age at diagnosis was about 60.1

Many patients are diagnosed after routine labs show a cholestatic pattern, then confirmed with disease-specific antibodies (often antimitochondrial antibodies) and clinical evaluation.4 Symptoms vary, and can include fatigue and pruritus, with some patients remaining relatively asymptomatic for long periods.4

Current drugs used to treat or manage primary biliary cholangitis

The PBC treatment landscape has shifted quickly in the past two years, which has real implications for evidence generation.

- Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA/ursodiol) remains foundational therapy and is recommended in major guidelines.4 It is used to slow disease progression and improve outcomes for many patients.2,4

- Elafibranor (IQIRVO) received FDA accelerated approval for adults with PBC who have an inadequate response to UDCA, or as monotherapy in patients who cannot tolerate UDCA.

- Seladelpar (LIVDELZI) also received FDA accelerated approval for a similar population: adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, or as monotherapy when UDCA is not tolerated.

- ❌ Obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) was rapidly pulled from the market in 2025 after real-world data identified serious liver injury risks in some patients.5-7

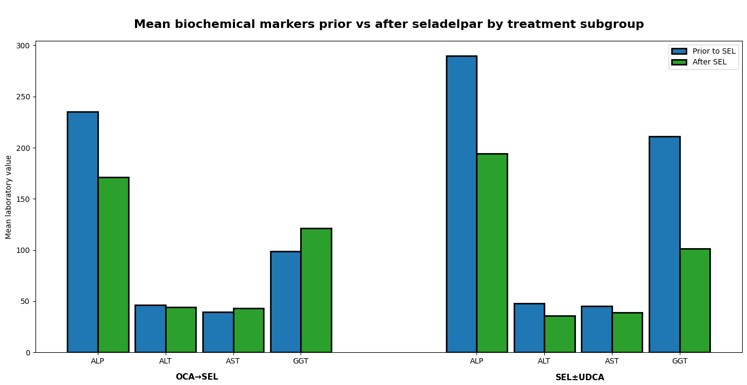

Obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) illustrates why this matters. Post-approval real-world experience identified serious liver injury risks in some patients without cirrhosis, prompting an FDA Drug Safety Communication in late 2024 and a voluntary U.S. market withdrawal in 2025.5-7 The withdrawal of obeticholic acid from the U.S. market created a therapeutic disruption for patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to ursodeoxycholic acid, while the 2024 approval of seladelpar introduced a new second-line option into routine practice (Figure 1).

This rapid transition has shifted real-world treatment pathways faster than traditional evidence generation can adapt, increasing the need for timely, longitudinal data to understand how patients are switching therapies, how biochemical response evolves outside trials, and where unmet need persists.

Figure 1: Real-world data suggest seladelpar may be a suitable option for PBC patients switching from obeticholic acid and as second-line therapy, though longer-term follow-up is needed to fully characterize outcomes. Created using data from Bowlus et al., 2025 using RWD and lab data from HealthVerity Marketplace.11

UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid; SEL: Seladelpar; OCA: obeticholic acid; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Current research in PBC and how real-world data is being used

Earlier diagnosis and better risk stratification

Because progression can be slow and heterogeneous, a major research focus is predicting “who will progress” and “how fast,” using markers that are measurable in practice. Guidelines emphasize risk stratification, and the field has developed validated prognostic models like the GLOBE and UK-PBC scores, built from large multi-center cohorts and using lab-based variables after UDCA treatment.7

That is an early example of what real-world data can do well in PBC: combine longitudinal follow-up with routine labs to translate biology into decision-grade risk estimates.

Real-world effectiveness and safety of therapies, including after accelerated approvals

With multiple therapies now in play, research questions are more operational:

- Which patients are starting UDCA promptly after diagnosis?

- How often do patients switch or add-on therapy?

- What does biochemical response look like outside trial populations?

- What safety signals emerge in broader populations, and how quickly?

Burden of illness and HEOR questions that trials do not answer well

Trials are not designed to quantify the full economic and utilization burden across years of care. Claims-based studies have been used to estimate healthcare resource utilization and costs by line of therapy, and to compare untreated vs treated cohorts in real-world practice.8

That work is helpful for payer and market access questions, but it also surfaces a common rare disease reality: you can estimate costs and utilization at scale, yet still miss key clinical context like lab-based disease activity or symptom severity.

Data gaps and challenges in PBC research, especially in rare diseases

Even with strong scientific momentum, PBC evidence generation runs into familiar rare disease barriers:

- Small, fragmented cohorts: Even when prevalence is measurable, the number of “analysis-ready” patients shrinks quickly once you require clean longitudinal follow-up, confirmatory diagnostic signals, therapy exposure windows, and sufficient outcomes time.3

- Missing clinical detail in claims-only datasets: PBC progression and treatment response are often assessed with lab markers (for example alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin) and other clinical variables that may not exist in claims.4,7

- Inconsistent monitoring in routine care: In practice, recommended testing can be uneven, which introduces missingness and makes response evaluation harder. A recent BMJ Open Gastroenterology study highlights that guidelines recommend regular ALP testing to monitor progression and UDCA response, and that adherence to recommended testing intervals can be low.9

- Bias and representativeness issues: Specialty-center cohorts can overrepresent complex patients or advanced disease, which shifts estimates for burden, outcomes, and treatment response. This is not unique to PBC, but it is amplified in rare diseases.10

- Identity and continuity challenges: When a disease requires multi-year follow-up, insurance churn and site-of-care changes can distort “real” outcomes if the patient journey is not stable across sources.

These are not just methodological concerns. They determine whether a study yields confident, reproducible conclusions, or ends with “insufficient N,” inconsistent endpoints, and results that are difficult to defend.

Recent real-world evidence from HealthVerity Marketplace evaluated seladelpar use in nearly 400 patients with primary biliary cholangitis, including those who switched from obeticholic acid after its U.S. withdrawal and those initiating seladelpar as second-line or monotherapy.11 (Figure 1). Across both groups, seladelpar use was associated with meaningful reductions in alkaline phosphatase and high rates of biochemical response, with safety laboratory results remaining stable over short-term follow-up. While follow-up remains limited, these findings illustrate how real-world data can rapidly inform treatment effectiveness and safety in evolving PBC care pathways.11

Where real-world data can go further in PBC and where taXonomy Pathways can help

If you are trying to generate decision-grade evidence in PBC, the question is not only “Do we have data?” It is “Do we have enough of the right data, for long enough, in a way that holds up under scrutiny?”

This is where a rare disease-ready approach to real-world data starts to matter.

taXonomy Pathways was built to unify closed payer claims with lab results and electronic health records (EHR), including physician notes, into research-ready, therapeutic area-specific datasets designed to close evidence gaps.1 In rare diseases specifically, Pathways is intended to bring scale and clinical depth together, without trading off privacy or rigor.12

Below is how that translates to the common evidence problems in PBC.

Volume: feasibility and power for rare cohorts

Rare disease studies often fail before they start because the cohort disappears after eligibility criteria are applied. taXonomy Pathways is anchored by closed payer claims spanning hundreds of payers, nine years of adjudicated history, and more than 300 million patients across pay types.12 That kind of scale can make the difference between a feasible PBC design and an “insufficient N” outcome once you require diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up windows.

Representativeness: checking referral-center bias

PBC care can concentrate in hepatology specialty settings, which can skew observed progression rates, complication patterns, and costs compared to broader community care. Pathways is designed around multi-payer claims coverage across pay types, which supports comparisons that can test how estimates shift by site of care and patient mix, rather than assuming one setting represents all.12

Longitudinality: monitoring outcomes that take years to show up

PBC is a long-run disease. Questions about progression to cirrhosis, decompensation, transplant, and long-tail cost are inherently longitudinal. With nine years of claims history plus aligned lab and EHR signals, Pathways is positioned for studies that need extended follow-up to capture outcomes that trials often cannot observe at scale.12

Stability: reducing small-N instability from cohort churn

In rare disease research, minor cohort churn can change cost and outcomes estimates more than teams expect, especially when follow-up is long. A stable longitudinal patient journey across data sources reduces noise and supports reproducibility, which matters when study results will be used in regulatory, payer, or internal governance settings.

Clinical depth: improving endpoint capture beyond claims-only

PBC research depends heavily on lab-based measures and symptom context. taXonomy Pathways includes lab results from two leading outpatient labs representing more than 60% of U.S. testing, with lab values and collection dates aligned to exposure windows from medical and pharmacy claims.11 It also incorporates more than 3.6 billion de-identified clinical notes across 340 million encounters for 43 million patients, capturing symptom-level detail and clinical context that claims do not capture well.12

For PBC, that opens the door to more complete real-world measurement of:

- Lab-based disease activity and response signals that define endpoints in many studies.4,7

- Symptoms and reasons for discontinuation that may sit in unstructured notes rather than coded claims.

- More credible comparisons of burden and outcomes when the “why” behind a treatment change matters.

If you are building PBC evidence and running into small cohorts, missing labs, or inconsistent longitudinal follow-up, request a taXonomy Pathways walkthrough to see how claims, lab results, and EHR notes can come together into a research-ready PBC patient journey.

References

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Primary biliary cholangitis: Definition & facts. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/primary-biliary-cholangitis/definition-facts

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Primary biliary cholangitis: Treatment. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/primary-biliary-cholangitis/treatment

- Tan JJR, Chung AHL, Loo JH, et al. Global Epidemiology of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2025.03.025

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Journal of Hepatology. 2017. https://easl.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PBC-English-report.pdf

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Drug Safety Communication (12/12/2024): Serious liver injury being observed in patients without cirrhosis taking Ocaliva (obeticholic acid) to treat primary biliary cholangitis. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/serious-liver-injury-being-observed-patients-without-cirrhosis-taking-ocaliva-obeticholic-acid-treat

- Intercept Pharmaceuticals. Intercept Announces Voluntary Withdrawal of OCALIVA for Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) from the US Market; US Clinical Trials Involving Obeticholic Acid Placed on Clinical Hold. September 11, 2025. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/09/11/3148535/23024/en/Intercept-Announces-Voluntary-Withdrawal-of-OCALIVA-for-Primary-Biliary-Cholangitis-PBC-from-the-US-Market-US-Clinical-Trials-Involving-Obeticholic-Acid-Placed-on-Clinical-Hold.html

- Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/PracticeGuidelines-PBC-November2018_1.pdf

- Kumar S, Shamseddine N, Yang H, et al. Economic Burden of Primary Biliary Cholangitis by Line of Therapy in the United States. Advances in Therapy. 2025. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12325-025-03439-6

- Gordon SC, Sahota A, Schmidt MA, et al. Assessment of adherence to guidelines for biochemical monitoring and ursodeoxycholic acid treatment response in a retrospective cohort of US patients with primary biliary cholangitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2025-001899

- Heredia S, et al. Real world data for rare diseases research: The beginner’s guide to registries. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2023. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/21678707.2023.2241347

- Bowlus C, Gordon S, Beltran T, Shen R, Xia F, Kotowsky N, Crittenden D, Frenette C, Chee G, Gao S. Abstract 5037: Real-world experience of seladelpar among patients with primary biliary cholangitis, including patients switched from obeticholic acid. AASLD. 2025 https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2025-11/HEP-D-25-00020-1.pdf

- HealthVerity. HealthVerity announces taXonomy Pathways: Closing evidence gaps with the most comprehensive patient journeys. October 7, 2025. https://healthverity.com/news/announcing-taxonomy-pathways/

- Bowlus C, Gordon S, Beltran T, et al. Real-world experience of seladelpar among patients with primary biliary cholangitis, including patients switched from obeticholic acid. Abstract 5037. Presented at: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Liver Meeting; 2025. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2025-11/HEP-D-25-00020-1.pdf